Every year, approximately 30 million people in the United States are occupationally exposed to hazardous noise. Noise-related hearing loss has been listed as one of the most prevalent occupational health concerns in the United States for more than 25 years. Thousands of workers every year suffer from preventable hearing loss due to high workplace noise levels. Since 2004, the Bureau of Labor Statistics has reported that nearly 125,000 workers have suffered significant, permanent hearing loss. In 2009 alone, BLS reported more than 21,000 hearing loss cases.

Exposure to high levels of noise can cause permanent hearing loss. Neither surgery nor a hearing aid can help correct this type of hearing loss. Short term exposure to loud noise can also cause a temporary change in hearing (your ears may feel stuffed up) or a ringing in your ears (tinnitus). These short-term problems may go away within a few minutes or hours after leaving the noisy area. However, repeated exposures to loud noise can lead to permanent tinnitus and/or hearing loss.

Loud noise can also create physical and psychological stress, reduce productivity, interfere with communication and concentration, and contribute to workplace accidents and injuries by making it difficult to hear warning signals. Noise-induced hearing loss limits your ability to hear high frequency sounds, understand speech, and seriously impairs your ability to communicate. The effects of hearing loss can be profound, as hearing loss can interfere with your ability to enjoy socializing with friends, playing with your children, or participating in other social activities you enjoy, and can lead to psychological and social isolation.

How does the ear work?

When sound waves enter the outer ear, the vibrations impact the ear drum and are transmitted to the middle and inner ear. In the middle ear three small bones called the malleus (or hammer), the incus (or anvil), and the stapes (or stirrup) amplify and transmit the vibrations generated by the sound to the inner ear. The inner ear contains a snail-like structure called the cochlea which is filled with fluid and lined with cells with very fine hairs. These microscopic hairs move with the vibrations and convert the sound waves into nerve impulses–the result is the sound we hear.

Exposure to loud noise can destroy these hair cells and cause hearing loss!

What are the warning signs that your workplace may be too noisy?

Noise may be a problem in your workplace if:

- You hear ringing or humming in your ears when you leave work.

- You have to shout to be heard by a coworker an arm’s length away.

- You experience temporary hearing loss when leaving work.

How loud is too loud?

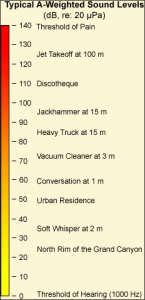

Noise is measured in units of sound pressure levels called decibels, named after Alexander Graham Bell, using A-weighted sound levels (dBA). The A-weighted sound levels closely match the perception of loudness by the human ear. Decibels are measured on a logarithmic scale which means that a small change in the number of decibels results in a huge change in the amount of noise and the potential damage to a person’s hearing.

OSHA sets legal limits on noise exposure in the workplace. These limits are based on a worker’s time weighted average over an 8 hour day. With noise, OSHA’s permissible exposure limit (PEL) is 90 dBA for all workers for an 8 hour day. The OSHA standard uses a 5 dBA exchange rate. This means that when the noise level is increased by 5 dBA, the amount of time a person can be exposed to a certain noise level to receive the same dose is cut in half.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has recommended that all worker exposures to noise should be controlled below a level equivalent to 85 dBA for eight hours to minimize occupational noise induced hearing loss. NIOSH has found that significant noise-induced hearing loss occurs at the exposure levels equivalent to the OSHA PEL based on updated information obtained from literature reviews. NIOSH also recommends a 3 dBA exchange rate so that every increase by 3 dBA doubles the amount of the noise and halves the recommended amount of exposure time.

Here’s an example: OSHA allows 8 hours of exposure to 90 dBA but only 2 hours of exposure to 100 dBA sound levels. NIOSH would recommend limiting the 8 hour exposure to less than 85 dBA. At 100 dBA, NIOSH recommends less than 15 minutes of exposure per day.

In 1981, OSHA implemented new requirements to protect all workers in general industry (e.g. the manufacturing and the service sectors) for employers to implement a Hearing Conservation Program where workers are exposed to a time weighted average noise level of 85 dBA or higher over an 8 hour work shift. Hearing Conservation Programs require employers to measure noise levels, provide free annual hearing exams and free hearing protection, provide training, and conduct evaluations of the adequacy of the hearing protectors in use unless changes to tools, equipment and schedules are made so that they are less noisy and worker exposure to noise is less than the 85 dBA.

What can be done to reduce the hazard from noise?

Noise controls are the first line of defense against excessive noise exposure. The use of these controls should aim to reduce the hazardous exposure to the point where the risk to hearing is eliminated or minimized. With the reduction of even a few decibels, the hazard to hearing is reduced, communication is improved, and noise-related annoyance is reduced. There are several ways to control and reduce worker exposure to noise in a workplace.

Engineering controls that reduce sound exposure levels are available and technologically feasible for most noise sources. Engineering controls involve modifying or replacing equipment, or making related physical changes at the noise source or along the transmission path to reduce the noise level at the worker’s ear. In some instances the application of a relatively simple engineering noise control solution reduces the noise hazard to the extent that further requirements of the OSHA Noise standard (e.g., audiometric testing (hearing tests), hearing conservation program, provision of hearing protectors, etc…) are not necessary. Examples of inexpensive, effective engineering controls include some of the following:

- Choose low-noise tools and machinery (e.g., Buy Quiet Roadmap (NASA)).

- Maintain and lubricate machinery and equipment (e.g., oil bearings).

- Place a barrier between the noise source and employee (e.g., sound walls or curtains).

- Enclose or isolate the noise source.

Administrative controls are changes in the workplace that reduce or eliminate the worker exposure to noise. Examples include:

- Operating noisy machines during shifts when fewer people are exposed.

- Limiting the amount of time a person spends at a noise source.

- Providing quiet areas where workers can gain relief from hazardous noise sources (e.g., construct a sound proof room where workers’ hearing can recover – depending upon their individual noise level and duration of exposure, and time spent in the quiet area).

- Restricting worker presence to a suitable distance away from noisy equipment.

Controlling noise exposure through distance is often an effective, yet simple and inexpensive administrative control. This control may be applicable when workers are present but are not actually working with a noise source or equipment. Increasing the distance between the noise source and the worker, reduces their exposure. In open space, for every doubling of the distance between the source of noise and the worker, the noise is decreased by 6 dBA.

Hearing protection devices (HPDs), such as earmuffs and plugs, are considered an acceptable but less desirable option to control exposures to noise and are generally used during the time necessary to implement engineering or administrative controls, when such controls are not feasible, or when worker’s hearing tests indicate significant hearing damage.